2016 – A major shift happened in India. Unique Identity Authority of India (UIDAI) (a statutory authority established by Govt. of India) had notified the Aadhar authentication regulations – establishing the framework within which private enterprises could utilize its identity architecture for their transactions. Shortly thereafter, RBI and telecom regulator introduced amendments in their KYC regulations allowing Aadhar-enabled e-KYC to serve as a substitute for the cumbersome manual authentication process that was being followed. And Reliance Jio was able to create a world record by crossing 16mn new subscribers in its 1st month of operations, just relying on Aadhar paperless SIM activation. As the enthusiasm for Aadhar was growing, opposition to it rose to a crescendo in parallel. Activists, lawyers, politicians of every hue demanded the cancellation of the project – calling into question the technology that it had been implemented without legislative backing, and rather than providing benefits to the poor, it was resulting in exclusion. Opposition against Aadhar was largely focused on the privacy implications of the project. While defending the Aadhar project – the attorney general of the country had argued that India had no such thing as a fundamental right to privacy.

😧 How did we get here? 😧

Personal space is dear to us all. Just as some technologies enhanced privacy, others chipped away at it. Every time this happened, humans opposed the technology at first but made their peace with it eventually to benefit from the obvious good it could do. Aadhaar is one example of the many ways in which we have begun to use data in everything we do. While it has made it far easier to avail of services from the government and private enterprises than ever before, there are those who rightly worry about people’s private data being put to ill-use – and, worse, without consent. Rahul Matthan, the author of “Privacy 3.0 – Unlocking our Data-driven future”, is intrigued with the way Aadhar has been implemented – made him examine how changing technology influences our notions of privacy and called into question – how data must be regulated. Rahul Matthan is a lawyer who specializes in technology, media, and telecommunications – attempts to provide some explanation for how we have come to our current notions of personal space and individual privacy, starting from early human tribes to all the way down to our data-driven present where it seems there is little we can do to conceal our thoughts and actions from those around us. In the process, he re-imagines the way we should be thinking about privacy today if we are to take full advantage of modern data technologies, cautioning against getting so obsessed with their potential harms that we design our laws to prevent us from benefiting from them at all.

What is “Privacy”?

“Privacy is not of nature; it is born of technology and is unique to mankind.”

Let’s look at history and find out how technology is giving birth to privacy to humans…

In the jungle, humans started herding to reduce their vulnerability to surprise attacks by animals and predators. They had no personal space and knew everything there was to know about each other. The solitude and, consequently, privacy were not just acceptable among early human societies, they were downright dangerous to their survival. Solitude was a luxury enjoyed by only those few animals who occupy a position on the top of the food chain.

In time, humans began to figure out how to modify their natural environment and started settling down, building permanent camps, and developing social structures. During the transition from hunter-gatherer to farmers – the concept of privacy entered human consciousness. In doing so, it gave birth to the individual as an entity truly distinct from the community and allowed every human being to have a personality that was unique, which can be hidden from those around him.

Walls:

Walls allowed mankind – for the first time – to savor the benefits of privacy – where the man had a space into which he could retire and cast off the social expectation of constant vigilance. Once this happened, people were able to develop two distinct personas – one for public consumption and the other that they were allowed to surface within the confines of their home. It is the evolution of this split personality that our modern notion of privacy is rooted.

Role of Religion in enhancing ‘Privacy’

In the west, Church encouraged the idea that man should communicate privately with God in order to seek forgiveness. In 1215, the 4th council of the Lateran declared that confessions were mandatory and applied them to all. This practice subtly reinforced the notion that there are certain things in life that had to be kept confidential from everyone, including family members. And with that our modern notions of privacy were born.

While religion gave substance to the understanding that it was perfectly acceptable to keep confidences from one another, the principles of confidentiality took firm root in our dealings with each other e.g. lawyers, doctors. Privacy was finally given the status of a right by the courts along the lines of confidence and trust.

Technology – Privacy’s biggest nemesis

Technology has, time and again, butted heads with privacy, forcing us to constantly re-draw the boundaries of what we had previously believed to be our personal space. Technology has played a significant role in bringing us comforts and new benefits, but, at the same time, its many unintended consequences, particularly as they relate to matters of personal privacy, constantly make us question whether those benefits are at all worth it.

- Printing press – expose private writings and personal correspondence

- Camera – growth of yellow journalism and candid photography.

- Post and telegraph networks – ability to travel personal messages over pipes from centralised locations.

Every step along its evolutionary road, our notions of privacy have been shaped and formed by advancements in technology.

Privacy – 3 phases of evolution:

Privacy 1.0:

1st phase of privacy developed when the idea of personal space and private thoughts were discussed/disclosed with others in confidence. There were laws to protect the individuals in terms of breach of trust by the involved parties, but technology developed, this approach wasn’t nearly sufficient to protect our personal privacy from those beyond our immediate circle of trust as technology made it possible for complete strangers to invade our personal space.

Privacy 2.0:

Privacy 2.0 was about elevating it to the status of a right that could be exercised against anyone who impinged upon our privacy without our express consent i.e. consent-based protection. This is the construct upon which most of our existing laws have been based. It has served well from the time when data about us was kept in physical files to all the way down to the internet when everything began to be digitized.

Privacy 3.0:

Our world today is so rich with data that consent-based protection is proving ineffective against the onslaught of modern technologies. There is a need to re-imagine privacy laws to allow us to function in the modern data-driven world that we find ourselves in.

Privacy vs Identity – What’s next?

Let’s go back to Aadhar’s predicament. Despite its robust technological design and architecture, there are two fundamental shortcomings:

1) Aadhar project needed legal backing – a law regulating the manner in which the biometric data being collected and should be secured and most importantly, who would have access to it.

2) There is no privacy law in India. Once Aadhar became ubiquitous, the fear is that the government world or whoever has the authority, with minimal effort, be able to reach across its disparate databases and connect the scattered information about individuals. Disaster waiting to happen.

What are the implications? Let’s understand a few terminologies first:

Data subject: The individual that personal data relates to and gets collected.

Data Controller: The entity that alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the collecting and processing of personal data.

Currently, consent is the primary legal safeguard used to protect against privacy violation – i.e. no one should be allowed to use an individual’s personal information without his permission. All privacy laws around the world, without exception, have been designed on this basis.

Consent serves 2 purposes:

1) it gives data-subject autonomy over the use of his personal data, giving him the absolute power to decide whether or not to allow it to be used.

2) once consent has been properly obtained, it indemnifies the data controller from any violations of privacy or other harm that results from the use of that personal data.

As you see, the biggest flaw in the consent-based approach is – the portability of information has become ubiquitous.

What is Information?

Information has three facets:

a) Non-rivalrous – There can be simultaneous users of the piece of information. Use by one person at the same time doesn’t make it less available to another.

b) Invisible – Invasions of data privacy are difficult to detect because they can be invisible. Information can be accessed, stored, and disseminated without notice.

c) Recombinant – Data output can be used as an input to generate more data output.

Information has become more ubiquitous, utility-based, and inter-operable, hence more vulnerable to privacy attacks. Due to the nature of personal information in the era of Privacy 3.0, the current consent-based laws are not sufficient to protect us.

Following are the 3 reasons why consent is no longer a feasible means to safeguard privacy:

- Interconnection: Modern databases are designed to be interoperable – to interact with other datasets in new and different ways (via API that allow easy access to their datasets). This allows data controllers to layer multiple datasets in combinations that generate new insights but which at the same time, create privacy implications that no one can truly understand.

- Transformation: Machine learning algorithms take elements of non-personal data and make connections between them by spotting patterns and building complex personal profiles, transforming them in the process into deeply personal, often sensitive, data. Since, there is no need to seek prior consent to collect or process non-personal data, relying exclusively on consent as our only protection against privacy violation is ineffective against the harms that can result from the use of these algorithms.

- Consent-Fatigue: Consent worked as originally conceptualized because there were limited reasons to collect data and dew alternative uses to which it could be put. This is no longer the case. This, combined with sheer number of contracts we end up signing, leads to consent fatigue and diminished consent, we end up agreeing to terms and providing consent without actually understanding what we are consenting to.

Considering the above, how can the data-subject be expected to be held to the consent he has provided when it is impossible for him to fully understand the implications of giving such consent? It gives the data-subject a feeling of control which is completely meaningless, given how little we know about the data is being collected from us.

Existing Data Regulations

Although there are data regulations in the world (GDPR, CCPA) that are considering the sensitivity of the situations and to protect the individuals’ privacy – they are trying to make data controllers accountable by imposing heavy penalties (as much as 4% of global turnover in GDPR) on the event of a privacy breach. The problem with introducing heavy penalties is that – it is making data controllers over-cautious of being defaulters and it is stifling innovation in the data economy.

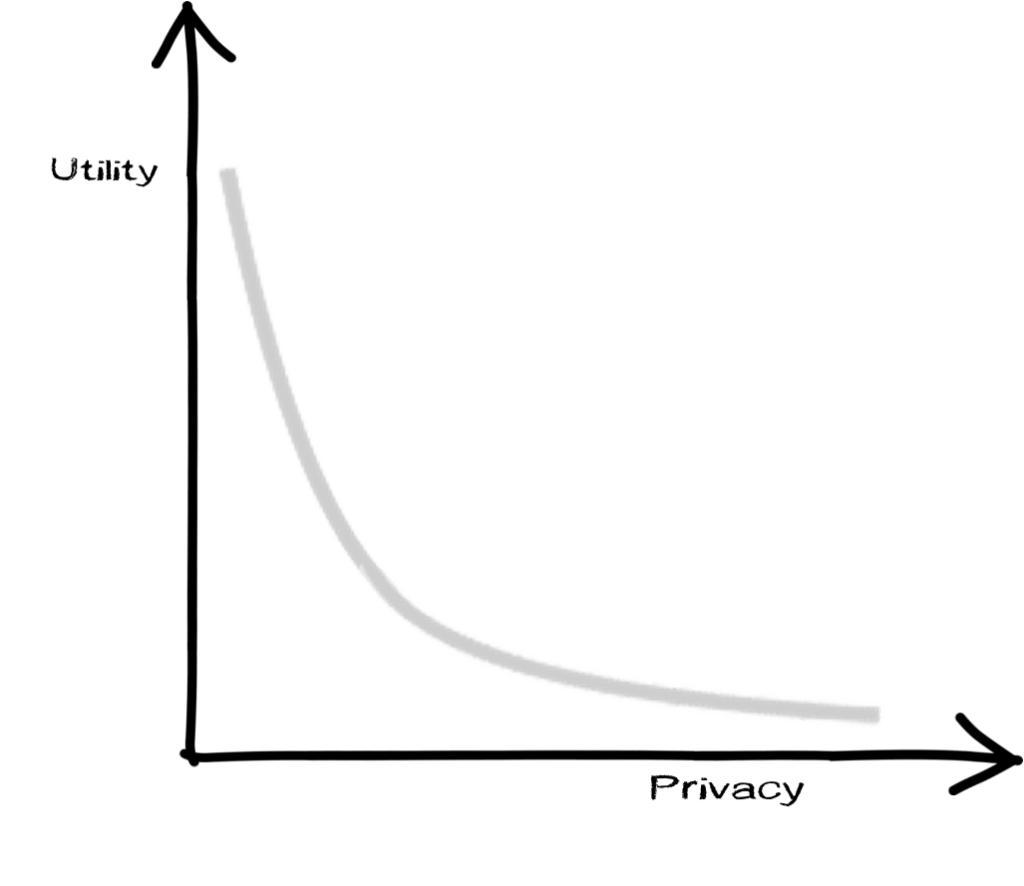

The consent-based approach is stifling innovation in data technologies and creating impediments to the free flow of data. The balance needs to be achieved between protecting individual privacy and freeing up data to properly inform our decision-making. If we can devise a form of protection that will encourage the data controllers to keep innovating with new and useful data-driven business models but at the same time protect privacy, we will have reset the balance. How can we do that?

Striking a balance between Innovation and Accountability

It is the data-controllers that are best placed to appreciate the impact that collection and processing of data can have on the data-subject since data-controllers have the full knowledge and control of the algorithms they use to process this data and when and under what circumstances they apply them. This is the basic premise behind the new accountability model – shifting accountability to data controllers. But the regulatory focus should be on remediation, rather than punishment i.e. instead of punishing data controllers for the inadvertent errors in their algorithms in their data processes, the emphasis should be on encouraging the data controllers to remediate in a timely fashion. They should only be penalized if they fail to remedy it in time. By doing this, we are allowing the data controllers the space to innovate with technologies as it is only out of such innovation that new technologies can develop.

However, even with the best intentions, it is possible that design flaws could slip through. To safeguard against this, the model needs to additionally include a construct by which data processes can be independently verified to assess whether any faulty processes that might have escaped the scrutiny of the data controller are influencing the outcomes. Rahul Matthan suggests the easiest way to implement this would be through an audit – creation of a new category of intermediaries structurally incentivized to operate in the interests of the data subject. They will audit the data practices of the data controllers, publish their findings, pointing outflows, if any., allowing an opportunity for data controllers to rectify the defects pointed out without punishment unless it is shown that they operated with malice aforethought.

Innovation and Accountability in designing Algorithms

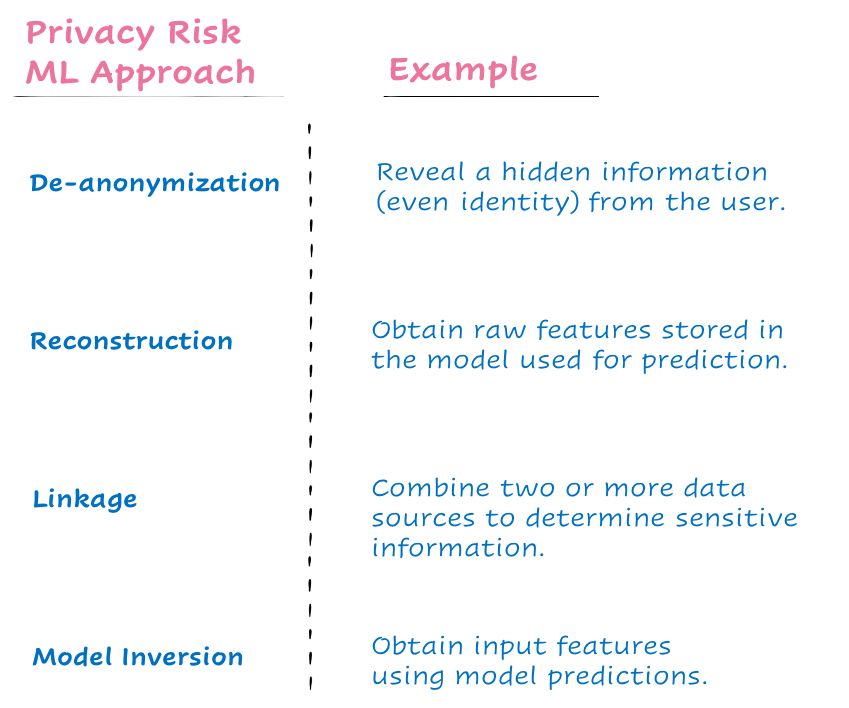

By creating an entirely new model for data protection based on accountability and audit, the author believes we will be able to address the data asymmetry that currently exists. There is still room for slips and errors of privacy leaks. Some of them are mentioned below:

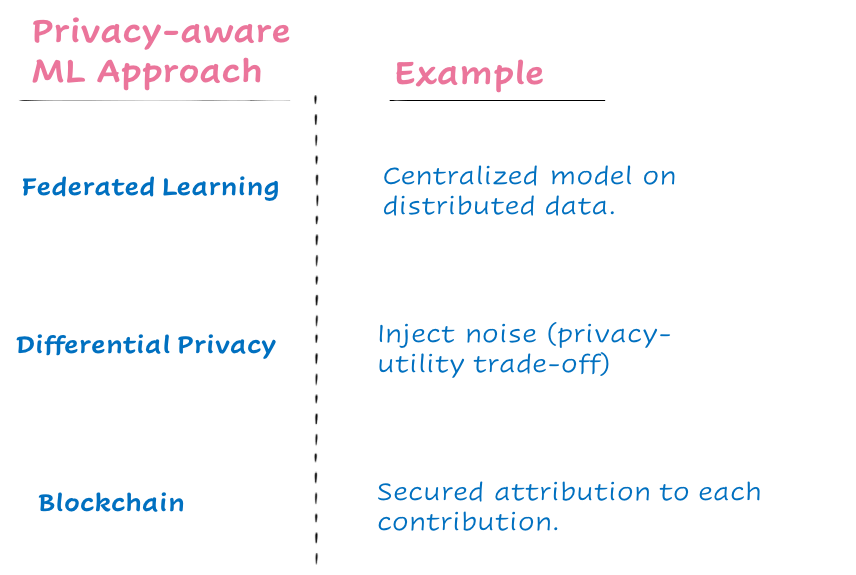

The knowledge gap between the machine-learning and privacy communities must be bridged using privacy-aware machine learning approaches, few examples are mentioned below:

The goal should be to construct training algorithms to obtain global deep learning models without aggregating data to a central cloud, that can be adapted to all data, even when individual nodes only have access to different subsets of the data.

References:

“Privacy 3.0 – Unlocking our Data-driven future” by Rahul Matthan

Swipe for more stories

Swipe for more stories

Comments